STORIES OF GROWING UP IN CALIFORNIA

Delfina’s Girlhood

Kumeyaay

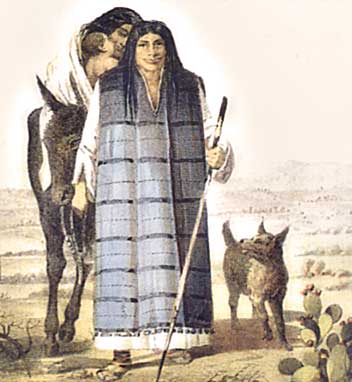

Delfina Cuero was born into a Kumeyaay family just before 1900.

She grew up in the old ways that her people always followed in the region north of modern San Diego. Her grandfather sang ancient songs and led ceremonial dances. Her grandmother, born at San Diego Mission, told stories about the old ways. Defina wasn’t interested in learning basket weaving from her grandmother but loved gathering plans and herbs with her.

Her family didn’t buy groceries at a store. They hunted and gathered food at the beach, from the ocean, meadows and forests. They harvested abalone, fish, shellfish, octopus and salt. She believed eating rabbit improved her eyesight. From the meadows and forests, Delfina harvested green vegetables and roots then boiled and dried them for storage. Pumpkins and sweet peas with red flowers were her favorite foods. Manzanita berry juice with honey was a special drink. Nuts flowers and grass seeds rounded out her diet.

Delfina’s life was hard but fun. She made dolls from rags with sticks for legs, or made dolls and tiny animals from clay Kumeyaay kids played hockey with balls of woven sticks. They shot bows and arrows and threw rabbit sticks, like boomerangs. Girls and boys staged mock battles using wild gourds for ammunition. Delfina was a great fighter and got into trouble for tearing her clothes. She was a fast runner and would jump off the highest rock to prove her bravery.

She was among the last Kumeyaay who grew up in the ways that her people lived for thousands of years. Today where Delfina Cuero gathered food and played games is where thousands of people live in communities north of San Diego.

Source: Delfina Cuero: Her Autobiography, an Account of Her Last Years, and Her Ethnobotanic Contributions (1991).

Lucy’s Salt Journey

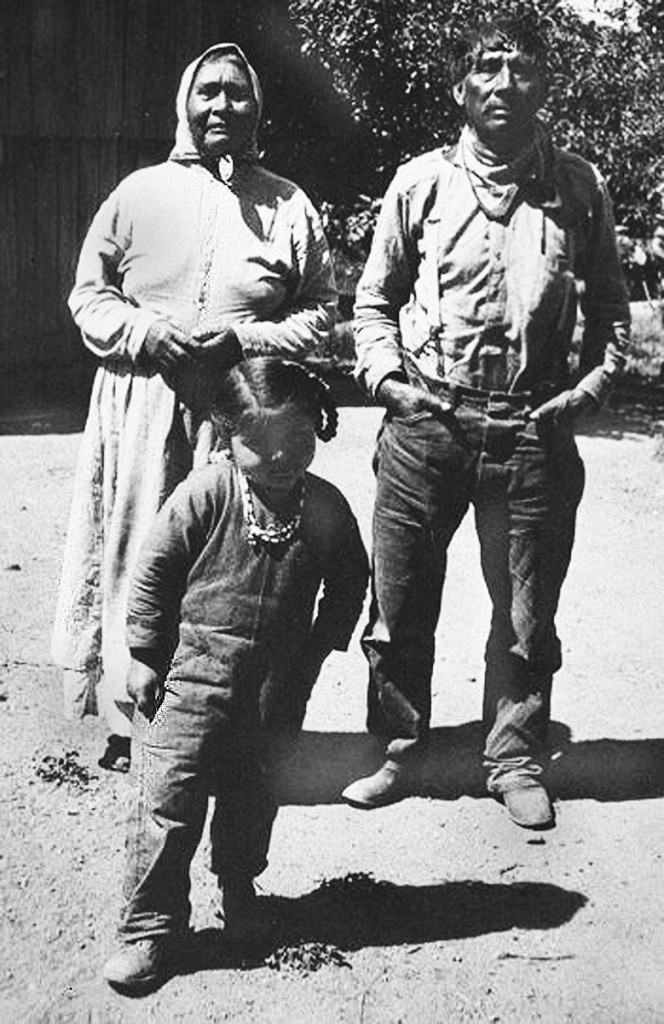

Lucy Young and Yellow Jacket at Round Valley

Lucy Young, who died in 1944, was born into a Wailaki tribe along the Eel River in the 1860s. She survived the soldiers and settlers destruction of her traditional community but never forgot the old way of life. Later in life, she lived in Round Valley, where people sought her out for her knowledge of the natural world.

She remembered that every year after the heavy rains they went to collect salt. Before they left, they stored roots and berries in pits dug in the ground or hung it in big baskets around the village, so animals did not get it, to make sure old people and nursing mothers who stayed behind had enough to eat.

Hunters brought in fresh meat for the stay-at-homes and to feed people on the first days of the salt journey.

The salt springs were on the land claimed by Wintu people, enemies to the east. Sometimes they traded for salt but liked to get it for themselves. They walked for a month to reach the salt country in the Yolla Bolly Mountains by the full moon. That way they had enough light to work at night to avoid their enemies. If they got there a day or more after the full moon, there was conflict.

Men walked barefoot. Big children and women wore knee-length moccasins. They fished and hunted as they traveled, search for bulbs and marked places to harvest them on the way back.

It they got to the salt creek before the full moon, they waited. Some women stopped with the big children at the edge of the salt country. Then when the moon was full, fast women runners and warriors silently raced to the salt springs. Salt lay crusted on the ground and covered low shrubs. They swiftly gathered salt from the ground and stripped it from branches into their baskets. If they were lucky, they gathered a year’s supply in one night. Then they did not need to trade for it.

Back in Wailaki territory, they stopped to clean the salt, pulling out sticks and stones, boiled the salt in baskets with cooking stones and poured off the dirty water. Salt formed a crust on top when the water cooled.

All the way home, they hunted and fished and gathered bulbs. When they met hunting parties from other villages, they visited, told stories, shared food. They wasted nothing, shared everything.

Lucy Young said the salt journey was like a walk through heaven.

Source: Indian Uses of Native Plants by Edith Van Allen Murphey (1959).

Juan Grows up in Monterey

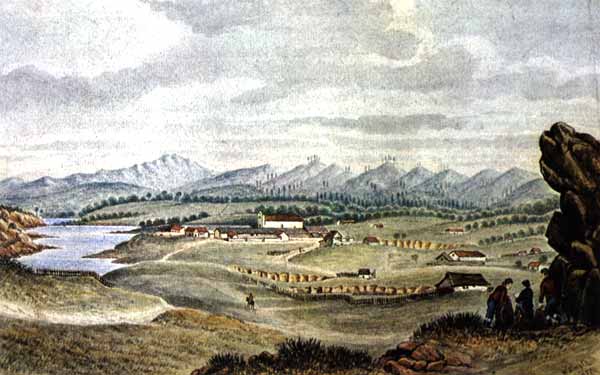

A watercolor by William Smyth during the winter of 1826-1827 shows a small number of scattered adobes without any formal property lines, fences, or streets. Courtesy of Monterey County Museum.

Juan Bautista Alvarado was born in Monterey in 1809. His father went from Mexico to Alta California as a soldier. He fell in love with and married Doña Maria Josefa, whose father was a soldier at the Presidio of Monterey. Juan was their only child.

Juan was two months old when his father died. He was on his way home from San Diego, carrying orders from the governor, when a fever took his life. As soon as Doña Maria learned he was ill, she rushed from Monterey with her baby. But the mission fathers had buried him by the time they reached Mission San Miguel. The people of Monterey were distressed by his death. Juan’s father was highly respected by his fellow soldiers.

Five years after being widowed, Doña Maria married Raimundo Estrada, a soldier at the Presidio of San Francisco. Juan was sent to live with his grandparents Vallejo. They loved him and did all they could to provide Juan with the best possible upbringing.

Before he died, Juan’s father left an order for the paymaster at Monterey to sell his horses and saddles and other trappings and turn the proceeds over to my mother. Half would be hers, the other half set aside for when Juan reached a suitable age. Six hundred pesos were collected. Considering his father’s young age, the short time since his arrival in Alta California and his military rank, Doña Maria’s situation seemed excellent.

In November 1818, the pirate Bouchard and his men burned Monterey, the capital of Alta California. Presidio families scattered and took shelter in the missions. Juan’s mother lodged with the padres at Mission San Juan Bautista.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Alvarado Bautista (1982).

Juan becomes a Rancher

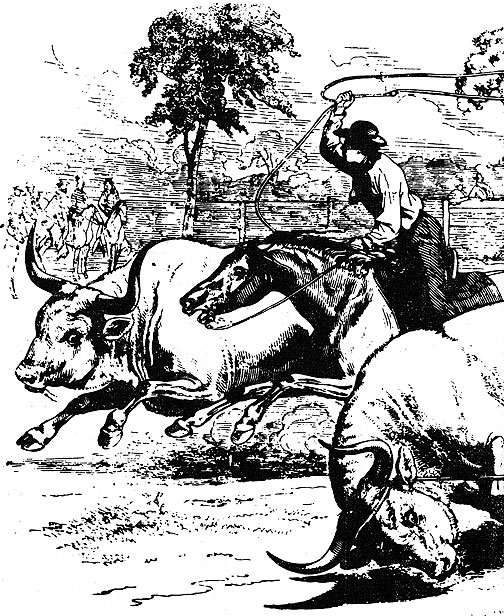

“Vaqueros Roping a Steer” by Charles Nahl (1866).

After the pirates burned Monterey, Juan’s family needed a place to live. His stepfather, Raimundo Estrada, was a famous hunter, so Don Ignacio Ortega, a rancher who lived near Mission San Juan Bautista, invited him to come hunt bears. Bears were devouring Don Ignacio’s livestock. Don Ignacio offered food and lodging. His stepfather accepted the offer on condition that Don Ignacio supply old horses as bait to hunt the bears and Estrada kept the bear skins. They agreed so Don Ignacio sent oxcarts to take them to his ranch.

Juan was delighted to become an apprentice rancher because he wanted to ride a horse and do farm work. Bear-hunting also appealed. Trading ship captains bought skins for 6 to 10 pesos each, depending on their quality. They took them to Mexico, where they sold at great profit. Mexicans decorated saddles and riding chaps with the skins, which they made deep black and pliable.

The eldest Ortega daughter was married but the others were about Juan’s age. Their grown son woke early every day to ride around the ranch. The younger daughters, Antonia and Clara, had hair that reached to their knees. They did all the housework and milked the cows early every morning.

Juan’s mother received part of the milk. He wanted to help, so she told him to go with the girls to the corral every morning. Juan had to take off his shoes and roll up his pants to his knees, because the corral was very muddy. He lassoed the cows by the horns so they could tie them to a post. The cows legs were tied at the knees, then a calf was then allowed to suck the first milk. Then the calf was taken away and they milked what they called the second milk, which had the greatest fat content and best taste.

My only problem was roping the wild cow.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Juan and the Wild Cow

Vaqueros.

At Don Ignacio’s ranch, among the dairy cows that his daughters, Antonia and Clara, and Juan milked, one was wild. It charged the girls and they had to climb the corral fence to escape. The girls said their brother tried to tame the cow but without success. Juan bravely told them that he could tame it and together they entered the corral.

As Juan was preparing to lasso the cow she tried to gore him. Fortunately he was standing close enough to the corral fence to climb up. The cow’s horns scraped the fence below his feet. The girls, who had been standing nearby also jumped up to safety.

Juan hatched a plan for taming that cow. “We’ll catch her and I’ll saw off her horns. Then she’ll have no way to gore anyone. When she finds herself without her natural weapons, she’ll lose her wildness. She depends on her horns to attack us. What will she do when she has only her muzzle to butt us with? She can’t kill us that way.”

Antonia asked, “How will we rope her afterward, to milk her?”

“By the neck,” Juan answered. “If she pulls and chokes herself, she’ll stop. Then she’ll obey the lasso.”

Antonia objected. “What will my father say?” “I think he’ll approve,” Juan answered, “provided he values your lives more than the horns of a cow.”

They agreed, so Juan told them, “Climb the fence with your ropes and I’ll bring in the cows so they pass right by where you’ll be. Lasso the wild cow, then wind the rope around a fence post. I’ll do the rest.”

Soon the cow was lassoed and tied to the post. Juan went for the saw and started the operation. When it was done, he rounded the edges of the stumps of her horns so that she could do no damage with them.

The following day the cow fled from us as though she were afraid that we would cut off some other part of her. In the end she became the best milker in the herd.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Juan the Storyteller

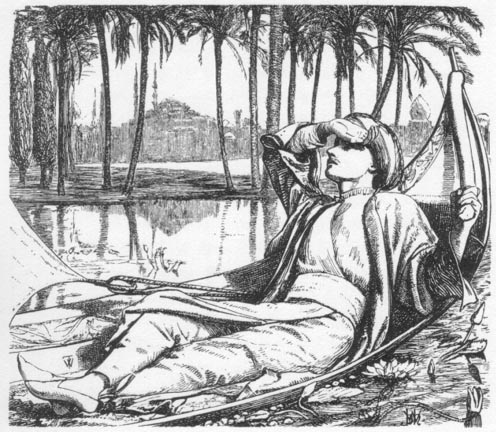

Engraving for The Arabian Nights by W. Holman Hunt (1857).

The nights seemed long that December at San Ysidro, Don Ignacio’s rancho. Juan often stayed at his house a good part of the night telling stories to the girls. They enjoyed tales from The Arabian Nights, to which he made additions. They invited him there every night, because, apart from the storytelling, they wanted Juan to give them lessons in reading and writing. He was just 9 years old, but could write a good letter and knew arithmetic.

The dogs on the ranch barked all the time, especially at night. This alerted the ranchers to thieves trying to steal their horses. That is why ranchers built their corrals close to their homes and shut up all their tame and usable horses at night; to protect them from attack.

Once, when Juan was in the most thrilling part of a story, the dogs began barking excitedly. Don Ignacio said, “Somebody’s out there.”

He and his son Julian Cantua and grandson Quintin took their shotguns, then went out to look in the direction in which the dogs were barking. Soon they heard some shots. They kept still and were a bit afraid.

After a little while Don Ignacio returned and told us. “There were horse thieves heading for the corral.” I asked him how he knew just by the barking of the dogs that it was people who were approaching the house. He answered, “It’s very easy to tell that. Ranchers know by the barking whether it’s people, bears, wolves or coyotes. When it’s a wolf or a coyote, the dogs bark as they head toward it. If it’s a bear, they bark without advancing or retreating. When it’s people, they bark in fear and draw back toward the house in search of protection.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Juan goes Hunting

Grizzly bear by Charles Nahl (1818-1878).

Juan’s stepfather wanted to begin the grizzly bear hunt as soon as the worst of the winter was over. When it did not rain, he scouted the countryside for hunting posts, always riding his trustworthy horse Coyote. Coyote was so used to gunfire that his stepfather could shoot over any part of the horse’s body without him moving. He was so concerned about Coyote’s fodder and water that he would not eat until his horse had. Sometimes he gave him sugar candy or tortillas from the kitchen.

To prepare Juan for the hunt, his stepfather had him mount Coyote. Riding one of the ranch horses, he lead him to the place where the hunt was to begin. They reached the edge of a wood, about a league from the house, where there stood a sturdy live oak in a clearing.

Juan’s stepfather said, “This is the starting point for our operations. I’ve already made a platform in this tree. You’ll bring me out here, leave then go home. At a set time, you’ll come for me again. Grizzly bears usually come out of their lairs at nightfall so there is no point in waiting for them once it gets very late. The platform has been set on two branches of the tree, and the palisade firmly lashed on. I’ll spend whatever time is necessary on the platform with my two guns. Bait for the bears has to be down below. That way I can shoot the bears from close range, so that my shots hit right by the foreleg and enter the heart. Just the same, when you come to take me home, don’t come up close to the tree. Whistle to me from a distance. When I answer you, and only then, can you come as close as you like.”

All these instructions, together with those he gave me at home, taught me what I had to do in this bearish enterprise. We returned home very late, and my mother asked me what I thought of the bear-hunting business. I told her that I already had all my instructions. I was determined to go ahead with it, since this business was lucrative and was going to make some money for us to take back to Monterey.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Juan Helps with the Laundry

Grizzly bear by Charles Nahl (1818-1878).

One day Juan’s mom asked him to help her with the laundry. They loaded the washboard onto Coyote and rode across the creek to her favorite laundry spot, a place sheltered from the wind and with plenty of clear water. Then they rode back to the house to get their the soiled clothes and a snack of mutton and tortillas. When they returned to their creekside laundry, Juan built a fire to prepare their snack.

Just as the smell of cooking mutton made Juan’s mouth water, he heard a grizzly growl in the woods. It frightened Coyote, who broke his halter then ran away. Juan shouted a warning to his mom and they raced to the creek. Juan held onto his mom’s shoulders and hair as she swam across. From the safety of the opposite bank, they watched the grizzly bear devour their snack. It ate even their laundry soap.

The following day, Juan’s stepdad moved the laundry to a safer spot closer to their house.

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Juan Gathers Wood

Rearing horse by Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630).

One day when there was no firewood in the house, Juan’s mother asked, “Juan, please take Coyote to bring a load of wood from the creek.” He had watched Don Ignacio’s son-in-law drag loads of wood, noticing how he tied the load, then pulled it with his rope, so Juan thought that would be simple. “There is no need for my stepfather to do this,” he told her. His stepfather was busy scouting the countryside to set up his bear-hunting stations. His mother accepted Juan’s offer but cautioned, “Be careful.”

Juan saddled Coyote and prepared ropes to tie the load, then went down to the woods. He collected thin pieces of wood and set them apart to form the load. When there was enough, he made a pile. Juan tied one end of the rope to the load, tied the other end tightly to the saddle horn, then mounted Coyote.

When Coyote took a few steps backward toward the load of wood, before he began to pull, the rope slipped between his legs. Juan did not notice this from the saddle but gave him a blow with the whip to start him moving.

Coyote reared so angrily that Juan flew into the air above the saddle, landing on his rump. Then he reared again and threw Juan onto the wood.

Coyote started to run. Juan clung to the wood, afraid to move and risk falling and getting hurt. He held on where his bad luck placed him. Coyote raced toward the ranch, pulling Juan along on top of the load. As the horse approached the buildings, Don Ignacio saw what was going on. He called to my mother, who rushed out of the house, frightened by the idea that Juan had an accident. Coyote came up to the door of the house with Juan on top of the wood, unable to move. Don Ignacio seized the horse’s reins. Juan’s mother helped him down from the wood, asking whether he was hurt. He was only scratched.

Don Ignacio told Juan, “You must not tie your rope firmly to the saddle horn. Just loop it around a couple of times so that you can loosen it in case of an accident like this. Remember that as part of your training as an apprentice rancher.”

Source: Vignettes of Early California: Childhood Reminiscences of Juan Bautista Alvarado (1982).

Pedro’s Math Book

Tablas para los Niños Que Empiezan a Contar (Monterey, 1836).

Pedro Castro was born in 1828, the fifth of nine children in a rancho family living near Monterey, the capitol of Alta California.

Some boys like him were sent to boarding schools in Hawaii to learn how to run their family rancho and conduct business with ships that visited Monterey to trade beautiful furniture, silks and other fine goods for cattle hides and tallow.

When he was 8-years-old in 1836, Pedro enrolled in Jose Mariano Romero’s school. one of the first in Alta California. Romero asked his friend, the printer Augustin Zamorano, to publish Tablas para los Niños Que Empiezan a Contar, meaning Tables for Children Learning to Count, on the press brought ashore two years earlier. This was the first school book in published in Alta California.

Pedro’s math book would be too difficult for many 8-year-old students today. He memorized the multiplication tables to the nines, learned to count to 1,000,000 by powers of ten, to make change using money in base 8, 12, and 24, to measure land and time concepts from a second to a century. Pedro even copied a formula for predicting the equinox on the back of his book.

Paper was scarce and expensive, so this book was printed on one piece of paper, then folded into 24 small pages. You can make a book like this. Hold a piece of paper lengthwise, like you are going to write on it. Fold the paper like a fan into thirds. Then fold the rectangle into half lengthwise twice and you have a square. Finish your book by opening then stapling it twice on the fold line. Then close it and cut the three outside edges. Make a paper cover by pasting a piece of softened brown paper bag pasted over the outsides.

Sally’s Overland Journey

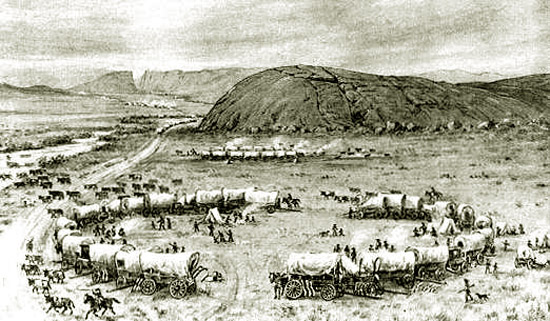

Independence Rock looking west with Devil’s Gate in the distance (1850).

Sally Hester crossed the Overland Trail to California in 1849 when she was 14-years-old.

With her parents, two brothers and sister, she left her Bloomington, Indiana home in March. They headed west with about 50 other wagons. Seven months later, just 13 worn out wagons rolled into the gold fields.

Their wagon train departed from St. Joseph, Missouri, in May and reached the Platt River, 315 miles from home, a month later. Cholera was rampant. Graves were everywhere along the trail. Crossing rivers was dangerous. Once when crossing the Truckee River, Sally panicked, jumped into the river and was swept downstream before being rescued.

Like hundreds of children on the trail, Sally scaled Independence Rock to find a place to carve her name. She also scampered up Devil’s Gate to look down on the Sweetwater River roaring through its gorge.

In September the Hesters passed the Donner Party’s tragic camp site. Sally saw two log cabins, bones and treetops sawed off to mark the depth of the snow in 1846. They marched over the crest of the Sierra Nevada that night, pine-knot torches blazing to light the trail.

Sally’s family set up winter quarters in a camp called Fremont, where the Feather and Sacramento Rivers converge. Christmas was dreary until some kids in camp invited her to a candy pull.

After the Hester family moved to San Jose, Sally met brown-eyed Patty Reed, who had come to California with the Donner Party and brought her doll. The girls, who had much in common, were good friends for many years.

Gold Rush Kids

Kids in one California gold camp found a clever way to get gold.

Miners there paid for stores supplies with gold dust. It was plentiful and easy to measure. They charged 1 ounce of dust for this, 2 for that – and if they didn’t have scales they charged by the pinch; 1 pinch of gold dust for this, 2 for that.

Miners would reach into the bag where they kept their gold, pinch out enough dust to pay and place it on the counter.

Some sharp-eyed kids who helped around the store noticed the same thing always happened when they did that. Gold dust trickled to the floor and as folks walked around the store, it disappeared between the floorboards. After a while they got an idea.

When the store closed one evening they went in with wash buckets, cleaned the floor and panned the dust from their water. Then with pins they dug the rest of it from between the floorboards. That day paid them well.

Source: Growing up with California: A History of California’s Children by John Baur (1978).

P.A., Boy Forty-Niner

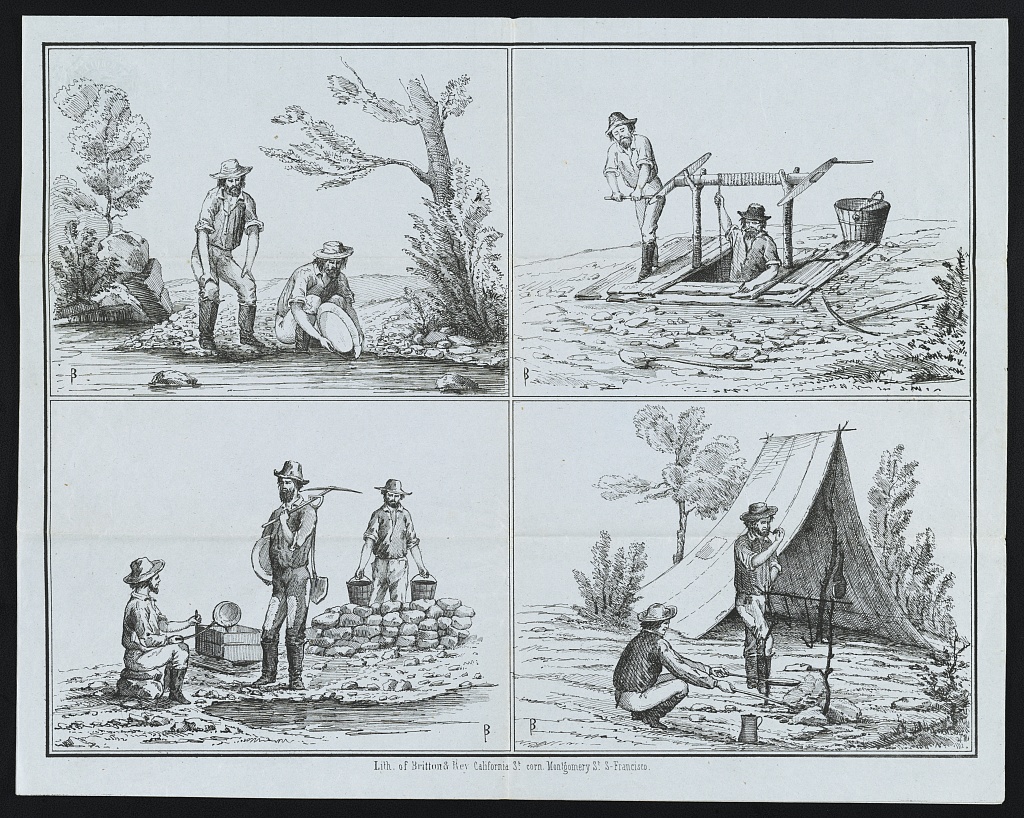

Miners panning for gold, entering a mine shaft, miners with equipment and miners cooking at camp (1850s). Lithograph by Britton & Rey.

P.A. Chalfant, always known by his initials, grew up quickly in the Gold Rush.

The wagon train that you P.A. was traveling with disbanded in the Sierras after six months on the Overland Trail. When he walked alone into a Feather River mining camp in October of 1849, all he had were the clothes on his back, a rifle, a blanket and a bit of food.

Always known by his initials, P.A. learned that gold mining did not always pan out. Until he could buy an iron skillet to wash gold from the river, he tried it with a canvas sack. Even with the skillet, he almost starved since he found less than a quarter of an ounce of gold a day. Anything to eat cost at least half an ounce of gold. A big breakfast cost more than four ounces at a mining camp hotel!

P.A.’s luck grew worse when the winter rains began. Wandering along the river one night, searching for shelter from a storm, he spied a small tent filled with miners eating flapjacks for dinner. They invited him to warm up by their fire but said their tent was “plumb full.” When the fire went out, P.A. spent a cold night dreaming of a blazing fireplace and the smells of a home cooked meal.

His life improved when P.A. reunited with some men from his wagon train. The old friends dug a shelter into the side of a hill, covered it with brush and timber then settled in for a long, wet winter in the mines.

Young America

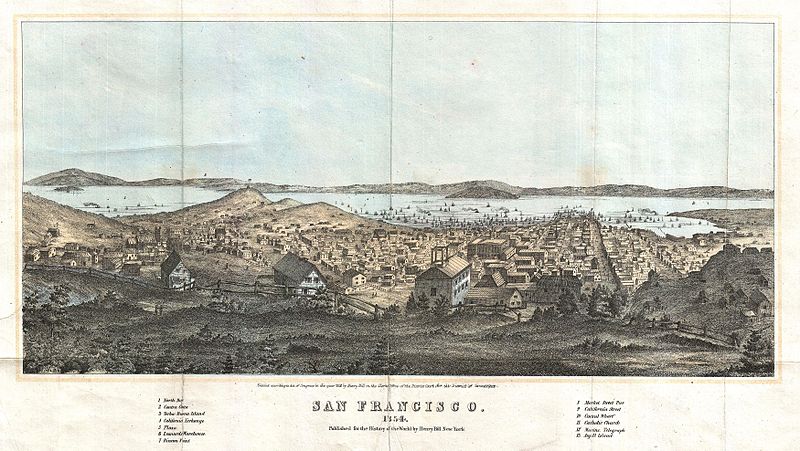

San Francisco (1856).

Gold Rush San Francisco had newspapers for kids. One was Young America, edited by 14-year-old James Perkins Tracy, who published it with the help of D.F. Verdenal and friends.

The four-page newspaper first appeared in October 1856. It looked like an adult newspaper but carried news and information for young readers, like school news. “In our last [week’s newspaper] we published a communication from “An Observer,” in relation to Mr. Holmes’ [a school principal] punishing one of the night scholars. We refrained from making any remarks on the subject, preferring to await an explanation. But Mr. H. has taken no notice of it whatever …” From their investigation, the editors concluded, “Mr. Holmes did punish in a violent manner … he had no right to punish any scholar of the night school.” Young America called upon the San Francisco Board of Education to “remove this man. Our youth are too precious to be guided by such a man.”

A reader wrote, “I see in the last number of that very regular sheet [newspaper] that goes under the very doubtful name of Star, that the Evening School is to have no vacation. I have an exceedingly poor opinion of the veracity of the aforesaid sheet and therefore ask you if this is so.” The editor looked into this then assured readers that Evening School would, in fact, have a vacation.

As its motto proclaimed, “Independent in All Things, Neutral in Nothing,” Young America was political. It supported 20-year-old Milton Latham’s campaign to become a United States Senator from California because “we go in for the youngest and at the same time more able men.”

Young America sold 500 copies a week. Businesses saw value in advertising in it. There were ads for a grocery, a bank, a furniture warehouse, a clothing warehouse, an alehouse and a druggist. In fact, it included so many ads, the editor apologized. “Our readers will observe that our colums [sic] are crowded with advertisements, and consequently much interesting matter is deferred. We intend keeping, for the benefit of our readers, at least two pages of original reading matter.”

James Perkins Tracy published Young America every Saturday until April 1857. Why it ended is a mystery. Another mystery is the newspaper’s price — “Twelve and a Half Cents.”

Sarah’s Los Angeles

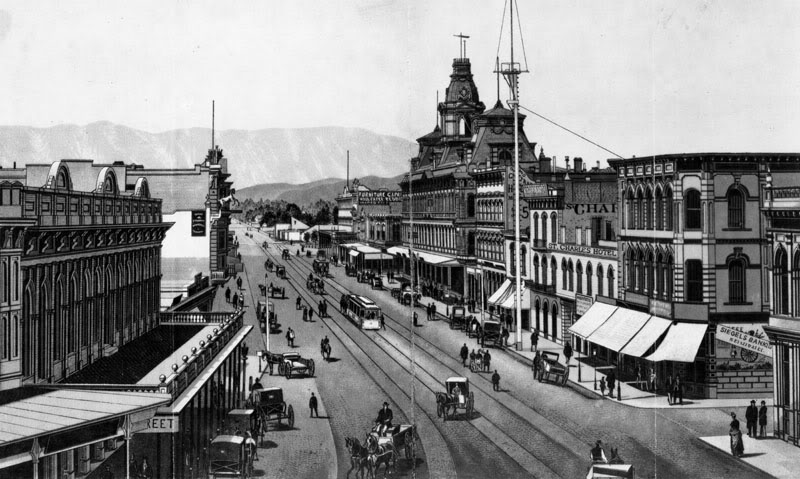

Main Street, Los Angeles. Baker Block is just right of center (1880s).

Sarah Bixby Smith had fun growing up in Los Angeles during the 1880s.

She shopped a lot. For dress-up and school shoes she went to a store called The Queen. If she wanted to window-shop for fine china and glassware, she strolled by the windows of Meyberg’s Crystal Palace. Stores along the Baker Block offered fine linens and laces, hats and bonnets, cutlery, watches and jewelry. Boston Store carried old-fashioned goods like people remembered buying on board Boston trading ships. Sarah liked that Mr. C.C. Parker’s book shop did not crowd its shelves with twine, glue, cosmetics and toys, not even school books.

On the Plaza in Los Angeles during the 1880s, when Sarah was a girl, Painless Parker practiced dentistry from a red and gold chariot with a throne-like chair for patients. In a nearby tent, Godfrey the photographer sat his subjects in a fringed red velvet chair with a brace to hold their head still so they would not appear blurry in their portrait. A Mexican ice cream man clad in white carried a freezer filled with his wares on his head. He held a circular tin tray with slots in the middle for spoons and holes around the edge for the cups in which he served his treats.

Los Angeles in the 1880s was a slow-paced small town. Two mule-drawn street cars carried passengers from downtown to Exposition Park, a few miles away. During the evening, the conductor would wind the reins around the brake handle and escort ladies to their front door.

Of all her memories, Sarah’s favorite was eating donuts twice a day.